The death of Bambi’s mother is a quintessential moment in dark Disney moments. She dies midway through the movie, horrifically, after we’ve gotten a chance to know her, after we’ve seen her raise Bambi and teach him the ways of the forest. A harsh winter follows a scant summer, and one day, when they’re out in the meadow grazing, she senses danger. There are hunters in the woods. Bambi’s mother tells him to run, to not turn back, and to keep running. They sprint. There’s the sharp crack of gunfire. When Bambi has made it safely back to the thicket, he turns, gleefully saying, “We made it, Mother.” There’s nobody but him. Alone, snow falling, he searches for his mother. He calls out for her, but there’s only silence. Later, he is told that she could no longer be with him.

Pinocchio is the story of the puppet who becomes a real boy. The trials he goes through to become a real boy are insane and trying: he is kidnapped by con artists and made to work in a puppet show lest he be thrown into a fire, and escapes only to find himself on Pleasure Island, an island where boys who “make jackasses of themselves” turn into literal donkeys and are sold to work in the salt mines and circuses. After escaping from Pleasure Island, he is swallowed by the giant whale that also swallowed Geppetto, his maker, who had been venturing out to rescue Pinocchio from Pleasure Island. They enrage the whale with their efforts to escape, and Pinocchio sacrifices himself to save Geppetto. The Blue Fairy, seeing his selflessness, brings him back to life and finally, turns him into a real boy.

It feels like a minuscule moment in a film about warfare, and I’m sure there are darker ones, but this short scene in Mulan always surprises me with its cruelty. Two Imperial scouts have been captured by Shan-Yu, the Hun leader, who gives them a message to take back to the Emperor of China. As they run away, Shan-Yu asks one of his comrades how many messengers it takes to deliver a message. Drawing back his arrow, his comrade answers, “One.” It’s not something I caught until rewatching it years later, but it’s so striking to see now, the way human life is treated so insignificantly between the two sides.

In the beginning, The Fox and the Hound feels like a charming, old-timey film about the way friendship transcends, but, somewhere in the third act, the story takes a sharp turn. Copper’s mentor Chief, gets hit by a train in a mishap caused by Tod. Copper vows to “get him.” Copper’s owner, Slade, sets traps, and soon, Tod is backed up in a burrow with fire on one end and Slade and Copper on the other. Tod leaps through the fire. Copper catches up with him. They clash, swiping at each other, snapping and howling, all remnants of their childhood friendship forgotten. Tod manages to escape when a black bear appears, and Copper rushes to defend Slade. But then, Tod turns back. He sees his old friend in distress, and lures the red-eyed bear down a rushing waterfall. The ending that follows is surprisingly adult and achingly bittersweet. Tod and Copper are in their respective homes. An old conversation plays—“We’ll always be friends forever, won’t we?” says Tod. “Yeah,” replies Copper. “Forever.”

The darkness in Lilo & Stitch is a very different kind of darkness than in other Disney movies, but still so significant as not to be overlooked. This darkness is about the hurt of a disjointed family, a broken family as Lilo says. After a comic, but ultimately disastrous visit from a social worker, Nani must prove that she is fit to care for her younger sister, Lilo. After she hears Lilo praying on a shooting star for a friend, she decides to get Lilo a pet. That pet—Stitch—turns out to be an alien. More disasters ensue with Stitch at the center of many of them. The social worker returns, telling Nani that the best option for Lilo might be one without her. That night, Stitch, seeing the trouble he has caused, leaves. Lilo tells him, “I’ll remember you; I remember everybody who leaves.” At its core, Lilo & Stitch is about loneliness, finding a place to fit in, about needing companionship and the families we create. Lilo & Stitch shows that sad, human darkness starkly, honestly and sincerely.

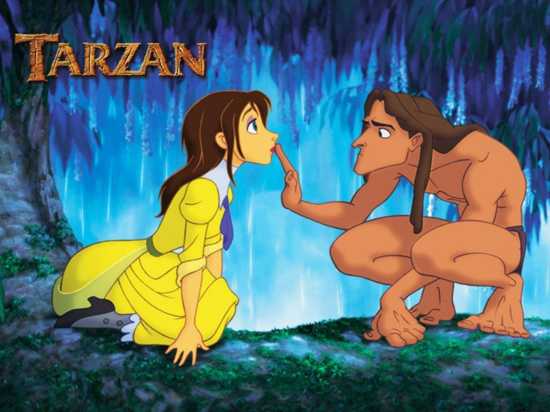

At this point of the film, Clayton’s motivations have been revealed. He plans to capture the gorillas and sell them in England, a task much easier with Tarzan out of the way. Clayton shoots Kerchak, a fatal wound, and Tarzan goes after a maniacal Clayton along the rainforest roof. After some struggling, Tarzan wrestles the gun away from Clayton, and has it pressed against his throat. Clayton dares Tarzan to shoot him, telling him to be a man. Instead, Tarzan destroys the gun, tossing it to the jungle floor. Clayton pulls out his machete and follows Tarzan across the vines, but in trying to slash Tarzan, he cuts away at the vines holding himself up. He cuts all but one—the one wound against his neck. There’s a short drop and a sudden stop. Against a flash of lightning, there’s a shadow—Clayton’s lifeless, hanging figure.

A surprising number of Disney movies have main characters with dead parents, or parents who simply aren’t there. In early Disney movies, their absences were rarely mentioned and never explained. There was Snow White’s missing parents, and Belle and Ariel’s missing mothers. In The Lion King, Simba has both his parents, but his father’s most climatic moment is his death. Not only is Mufasa’s death not mentioned in passing or in exposition during the length of the film, but on screen, and Simba is made to understand that he is responsible for that death. Mufasa’s murder is conniving, cold-hearted, and at the hand of Scar, his brother, who immediately drives Simba to run away, and subsequently sets hyenas to kill him. In the end, justice is served—Scar dies, and it is bolstered by Simba’s actions. And of course, there is Simba’s iconic Forever Alone moment, the subject of a thousand memes, when he, crying, crawls under his dead feather’s arm.

This song takes place at the height of the film, under circumstances that have cause to be on this list individually—the natives and the settlers on the cusp of war, Ratcliffe’s outright greed and racism compelling the settlers to march to battle, Powhatan seeking retribution for the death of Kocoum, Smith being led to execution. The intensity of lyrics like “what can you expect from filthy little heathens/here’s what you get when races are diverse/their skin’s a hellish red/they’re only good when dead” and “behind that milky hide/there’s emptiness inside/I wonder if they even bleed” are incredibly compelling for the first Disney film to deal openly with racism and imperialism, and although this story gets a happy ending of its own, there’s still a darkness and urgency in this song number that is unknown to other Disney films.

Like “Savages”, “Hellfire” is a villain song that touches on Disney taboos. Instead of racism, imperialism and war, however, these Disney taboos are sensuality, sex and rape—a far more forbidden fare for Disney. Judge Frollo, having just watched Esmeralda perform essentially a pole dance, and subsequently save Quasimodo from his punishment, is aroused and infuriated by her in equal parts, a scary combination. Consumed by lust, he seeks her out in the only way he knows how—by asking her to “choose me or your pyre.” Under the cloak of Tony Jay’s haunting voice, with lyrics like “destroy Esmeralda/and let her taste the fires of hell/or else let her be mine and mine alone” and to imagery that conveys the fierceness and fearsomeness of religion, “Hellfire” is a song of impending doom and a sad judge’s sexual frustration.

Considered Disney’s darkest animated motion picture, The Black Cauldron is the story of Taran, a young boy with dreams of heroism, who must find and destroy an enchanted black cauldron before the Horned King can use it to raise an army of the undead. The Black Cauldron was the first Disney animated feature to be rated PG for dark and violent images, one of which must have been the Horned King. Modeled after Satan in both temperament and appearance, the Horned King was a figure of calculated, unrelenting evil. Under his dark cloak, he was nothing more than a horned skeleton with glowing red eyes. The set too, was a frightening picture—a crumbling castle littered with rotted corpses, the dungeon where Taran is held early in the movie, a dank cellar where those of Cauldron born rise from the waters. As a whole, The Black Cauldron is a chilling and deeply unsettling movie, a well-deserved end to my list of dark Disney moments.