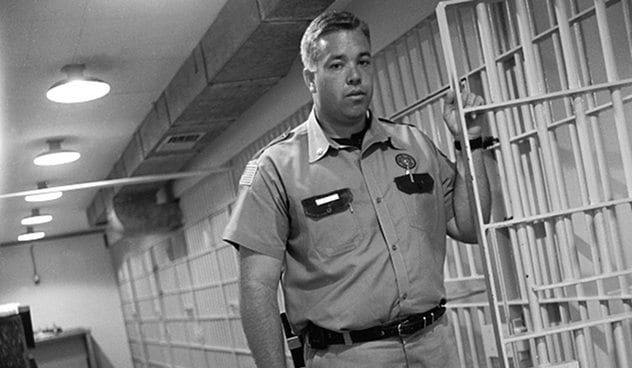

10Fred Allen

Fred Allen was a member of “the tie-down team” at Walls Unit Prison in Huntsville, Texas. He participated in some 120 executions, tying the inmates down to keep them still during their final moments. He reports, “I was just working in the shop and all of a sudden something just triggered in me and I started shaking . . . And tears, uncontrollable tears, was coming out of my eyes. And what it was was something triggered within and it just — everybody — all of these executions all of a sudden all sprung forward.” He left his job just after that. His boss at the time, Jim Willett, said, “I don’t believe the rest of my officers are going to break like Fred did, but I do worry about my staff. I can see it in their eyes sometimes . . .”

9Unnamed Wardens and Chaplains

Understandably, not all who participate in executions want their name to be shared, but they do share their stories. One such man, a warden, describes that the executed are offered the chance to say final words. A microphone descends from the ceiling. Some men pray, some sing, or profess their innocence. The warden said, “And then there have been some men who have been executed that I knew, and I’ve had them tell me goodbye.” Another warden describes the event, “You’ll never hear another sound like a mother wailing when she is watching her son be executed. There’s no other sound like it. It is just this horrendous wail. It’s definitely something you won’t ever forget.” Chaplains, while not executioners themselves, are usually present at the event. One reports, “I usually put my hand on their leg right below their knee, you know, and I usually give ’em a squeeze, let ’em know I’m right there. You can feel the trembling, the fear that’s there, the anxiety that’s there. You can feel the heart surging, you know. You can see it pounding through their shirt. . . . I’ve had several of them where I’m watching their last breath go from their bodies and their eyes never unfix from mine. I mean actually lock together. And I can close my eyes now and see those eyes. My feelings and my emotions are extremely intense at that time. I’ve never . . . I’ve never really been able to describe it. And I guess in a way I’m kind of afraid to describe it. I’ve never really delved into that part of my feelings yet.”

8Kenneth Dean

Kenneth Dean was the head of “the tie-down team” at Huntsville as of 2000 and he had then participated in 130 executions. He did not like to keep count. His daughter would ask him, “What is an execution? What do you do?” He said, “It’s hard explaining to a 7-year-old. She asked me, ‘Why do you do it?’ I told her, ‘Sweetie, it’s part of my job.’ ” “All of us wonder if it’s right . . . You know, there’s a higher judgment than us. You second-guess yourself. I know how I feel, but is it the right way to feel? Is what we do right? But if we didn’t do it, who would do it? . . . That was one part I had to deal with. You expect to feel a certain way, then you think, ‘Is there something wrong with me that I don’t?’ Then after a while you get to think, ‘Why isn’t this bothering me?’ It is such a clinical process. You expect the worst with death, but you don’t see the worst in death.”

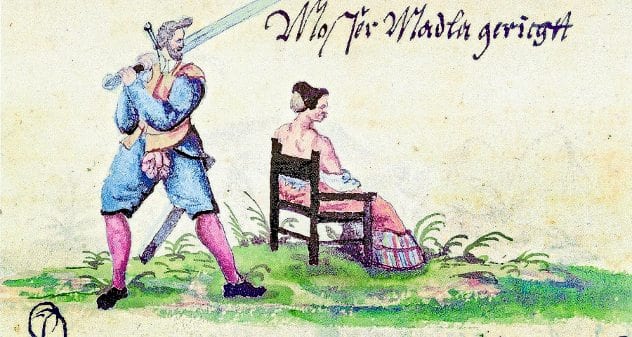

7 Meister Franz Schmidt

Meister Franz Schmidt worked as a professional executioner in Germany from 1573 to 1617, during which he maintained a personal journal. Schmidt, empowered by law, executed 361 people and tortured, maimed, flogged, burned, and disfigured many hundreds more. His journal describes each execution in detail: who was killed, what crime they had committed, and how the execution was carried out. His first entry, on June 5, 1573 reads, “Leonardt Russ of Ceyern, a thief. Executed with the rope at the city of Steinach. Was my first execution.” That entry set the tone for the rest of his journal, just cold facts, but over time the entries included more details and insights into the morality of Schmidt’s world. One entry, dated July 28, 1590 reports, “Friedrich Stigler from Nuremberg, a coppersmith and executioner’s assistant. For having brought accusations against some citizens’ wives that they were witches and he knew it by their signs. However, he wittingly did them wrong. Also said that they gave magic spells to people. Likewise for having threatened his brother, the hanged Peterlein, on account of which threat he had appeared before the court at Bamberg several years ago, but was begged off. Lastly, for having taken a second wife during the life of his first wife, and a third wife during the life of the second, after the death of the first. Executed with the sword here out of mercy.”

6 John Ketch

John Ketch was appointed as executioner in England in 1663 and soon gained a very particular reputation. He was apparently so bad at his work that it caused much public disdain, sometimes he took as many as eight strokes to behead a man. Public backlash was so strong against him, he wrote a letter in defense of himself, “But my grand business is to acquit myself and come off fairly as I can, as to those grievous Obloquies and Invectives that have been thrown upon me for not Severing my Lords Head from his Body at one blow, and indeed had I given my Lord more Blows then one out of design to put him to more than ordinary Pain, as I have been Taxt, I might justly be exclaim’d on as Guilty of grater Inhumanity then can be imputed even to one of my Profession, . . . But there are circumstances enow to clear me in this particular, and to make it plainly appear that my Lord himself was the real obstruct that he had not a quicker dispatch out of his world.” John Ketch blamed the man executed, Lord Russell, for why it took so many strokes. After yet another botched execution, one in which the man to be executed specifically asked not to be hacked up like Lord Russell, John Ketch was almost lynched but survived and his name became slang for lowlife executioners.

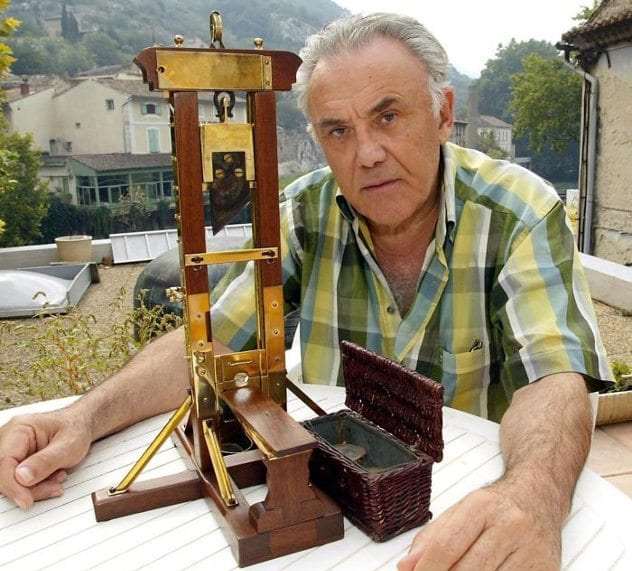

5 Fernand Meyssonnier

Fernand Meyssonnier, a second generation executioner and France’s last man to hold the position saw his first beheading at 16, with his father, who taught him the grim task. “He made me stand to one side so I wasn’t in the way.” Meyssonnier Reports, “Then we heard the call to prayer from the mosque round the corner and my father said, ‘It’s time’. The guy came out flanked by two guards. They pushed him on to the plank. I saw the head go between the two uprights, and then in a tenth of a second it was off. And at that moment I just let out a sound like this—Aaah! It was strong stuff.” In his published memoirs Meyssonnier discusses the executions that went wrong, the gritty details of a beheading, but also of his state of mind. He said, “It’s like a high speed film when the blade comes down. In two seconds it’s over. It gives you a feeling of power . . . You can’t think of the guy you’re guillotining. You have to concentrate on your technique. During the execution . . . I thought of the victims, what they went through. I was their means of vengeance.” In the decades since he stopped being an executioner, Meyssonnier’s view of the death penalty has changed and he is now opposed to it. “Three or four years after the execution,” He says, “the parent [of an executed criminal’s victim] will still want vengeance and won’t be able to have it. It is better to leave people in prison forever.” Meyssonnier also took up a new profession, “I got into a different form of execution—pest control.”

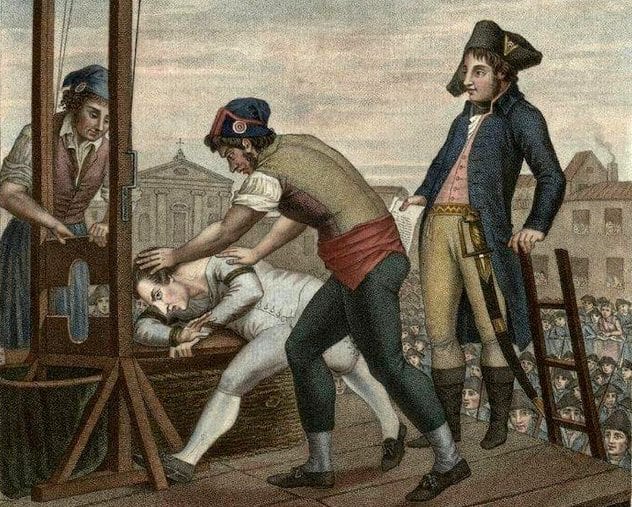

4 Henry Sanson

The Sansons were a family that supplied executioners to France for some 200 years. Henry, his father, and grandfather were all executioners and this heritage went back even further on his grandmother’s side of the family. His grandfather found it necessary to convince his would-be father-in-law that he could marry the daughter of an executioner and not despise her. The solution was to become an executioner himself. Two generations later and it was Henry’s turn. Henry wrote a record of his family’s deeds in the profession. In it, he spoke of their executions, the public reaction to them, and his family’s thoughts on the matters. One such execution was of a young man, 21 years old, who was accused of murdering his mother and one other to cover it up, in addition to theft. Sanson writes, “When we reached the prison of Bicetre, where the unhappy young man was incarcerated, we heard his cries through the walls of the cell when he was informed that death was at hand. He appeared in the hall, where we were waiting for him, supported by two warders. This was the first time I beheld such weakness before death. He said nothing while my assistants were cutting his hair, but when they undressed him he uttered frightful shrieks. The only words of his I could understand were ‘Mercy!’ ‘Pity!’ ‘I am innocent!’ ‘Do not kill me!’. He tried to rise, but could not. The black veil was spread over his head, and we started for the guillotine. Benoit fainted several times on the way. Whenever he recovered he exclaimed in a piteous tone: ‘M. Chaix d’Est-Ange has caused my death. My poor mother, you know I am innocent!’. The priest who supported him did not spare his encouragements, but Benoit still persisted in saying he was innocent. It was only when he saw the guillotine that he knelt and confessed his guilt. This confession I distinctly heard, although it was only intended for the ears of the priest, and I was relieved when it came out, for I had followed the trial, and in my humble judgment Benoit had been convicted on proofs which appeared to me anything but conclusive.” About his eventual retirement Sanson wrote, “My dismissal did come at last, and while some fifty eager individuals were competing for the office of executioner I greeted it as a deliverance.”

3 Henry Pierrepoint

A butcher, husband, and father to five children, Henry Pierrepoint carried out 99 executions over ten years for Britain, right up until 1910. He described one of these many executions, “With all the quickness possible we pinioned McKenna, and then was enacted a scene such as I will never forget as long as I live. The man knew that his last moments on this Earth had come. He broke out into great sobs and in the silence of that prison cell his voice wailed upward in one great tearing cry, ‘Oh Lord help me’. It was only a few steps to the fateful spot but McKenna walked slowly and falteringly—we could see that the strain was almost too much for the man we had to hang. Tears were rolling down his cheeks. The moment he toed the chalk mark on the scaffold he cried out aloud: ‘Lord have mercy on my soul!’ ” Henry Pierrepoint’s career ended abruptly when he arrived before a hanging very drunk. In that state he cursed his assistant and struck him, wanting to fight. His name was then removed from the approved list of hangmen. In his Home Secretary file is the note, “Make certain this fellow is never employed again.”

2Albert Pierrepoint

Albert, the son of Henry Pierrepoint, took up his father’s profession and executed some 400 men over the course of 15 years and resigned in 1956. Nine years later in 1965, capital punishment was ended in Britain, one year after the last execution. He wrote once, professionally detached, about his work, “Every person has a different drop. . . . Then in the morning at seven o’clock you go to the execution chamber again and get all ready, make the final arrangements for the job itself. Then we finish there about half an hour before the execution is going to take place, and that is all there is to it.” In his autobiography he shared his thoughts on capital punishment, “I have come to the conclusion that executions solve nothing, and are only an antiquated relic of a primitive desire for revenge which takes the easy way and hands over the responsibility for revenge to other people . . . The trouble with the death penalty has always been that nobody wanted it for everybody, but everybody differed about who should get off.”

1Jerry Givens

Jerry Givens was the Virginia state executioner from 1982 to 1999 and participated in executing the death penalty on 62 people. “If I had a choice, I would choose death by electrocution.” He said, “That’s more like cutting your lights off and on. It’s a button you push once and then the machine runs by itself. It relieves you from being attached to it in some ways. You can’t see the current go through the body. But with chemicals, it takes a while because you’re dealing with three separate chemicals. You are on the other end with a needle in your hand. You can see the reaction of the body. You can see it going down the clear tube. So you can actually see the chemical going down the line and into the arm and see the effects of it. You are more attached to it. I know because I have done it. Death by electrocution in some ways seems more humane.” As for why he stopped, he said, “To make a long story short, the grand jury said I was involved in money laundering and perjury for buying cars for my friend who obtained the money illegally. I told them I thought he had straightened out. But I did 57 months in a federal institution. I knew then that the system wasn’t right. I don’t believe I had a fair trial, so I realized maybe some of the people I executed weren’t given a fair trial.” When asked about his biggest mistake as an executioner he answered, “Biggest mistake I ever made was taking the job as an executioner. Life is short. Life only consists of 24 hours a day. Death is going to come to us. We don’t have to kill one another.”