As we will see, plastic surgeons have also been responsible for pioneering many life-enhancing procedures that go far beyond the cosmetic. But first, let’s answer the question that most of you likely have.

10 Its Name Has Nothing To Do With Plastic

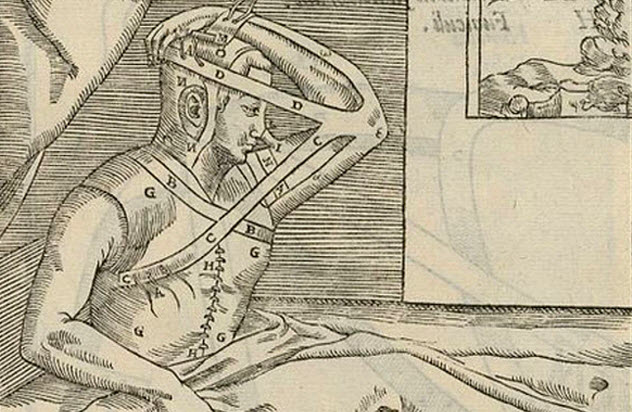

The documented beginnings of plastic surgery techniques date all the way back to the 16th century when Italian physician Gaspare Tagliacozzi—who was himself copying techniques described in an Indian manual written roughly 1,000 years earlier—successfully reconstructed the damaged nose of a patient using tissue from the inner arm. But the term “plastic” was first used to describe these techniques in 1837—a good 18 years before the invention of plastic, the substance. The term is from the Greek plastikos, meaning to mold or shape, and specialists in these techniques were initially far more focused on the reconstruction of misshapen or damaged body parts than cosmetic augmentation. By the mid-19th century, advances in anesthesia and sterilization had made it possible for more daring procedures, such as the original nose job, to be attempted. Throughout this time, however, plastic surgery was not formally recognized as a branch of medicine despite its obvious potential. And while it is true that its early focus was helping those disfigured by injury or disease, we will take a brief aside to answer your other obvious question.

9 Breast Augmentation Has A Longer History Than You Think

The first successful breast augmentation was likewise reconstructive rather than cosmetic as the patient had previously had a large tumor and a portion of her left breast removed. German surgeon Vincenz Czerny used a good-sized lipoma—a fatty, benign tumor—from the patient’s back to reconstruct the breast, and it’s safe to assume that the attempt was only able to be made because biological material from the patient was available to work with. This happened in 1895, and surgeons spent the next 70 years trying to come up with a viable material for commercial breast implants. Paraffin, alcohol-soaked sponges, and beeswax all failed to make the grade, but fortunately for breasts everywhere, Houston junior resident surgeon Frank Gerow came along in the early 1960s. Gerow conceived of the silicone implant after squeezing a blood bag and noting the similarity to a woman’s breast. His first experimental procedure was performed on a dog. It was successful, and before you ask, yes, the implants were removed once it was determined to be so. Timmie Jean Lindsey, his pilot human patient, was asked to volunteer for the procedure after coming in to consult about having a tattoo removed. She was thrilled with the results. As a testament to the viability of the procedure, she still retains her implants—the first ones ever—to this day.

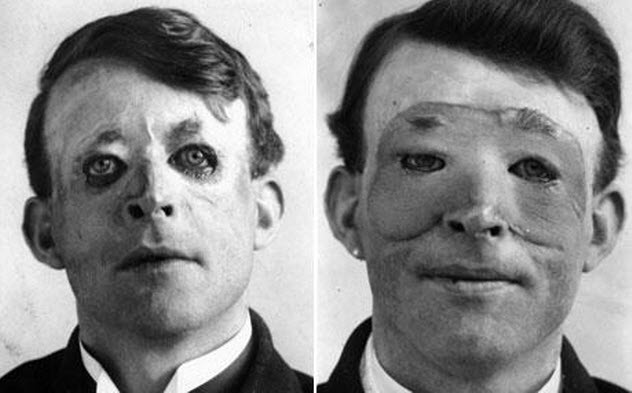

8 Modern Reconstructive Surgery Was Pioneered During World War I

While the aforementioned advances in anesthesia and antisepsis had plastic surgeons performing complex procedures on delicate areas by the early 1900s, the burgeoning specialty had never seen challenges such as those presented by World War I. Entire new categories of explosives and weapons were being deployed on the battlefield, and thousands of soldiers were returning home with the types of injuries that had literally never been seen before. It was in leading the response to these challenges that the field underwent perhaps its greatest sustained period of advancement, largely thanks to the efforts of New Zealand–born, London-based surgeon Harold Gillies, widely considered the father of modern plastic surgery. Recently uncovered records detail over 11,000 procedures performed on more than 3,000 soldiers in the eight years between 1917 and 1925, including groundbreaking skin and muscle grafting techniques that had never before been attempted. As antibiotics did not yet exist, infection was always a major concern. Dr. Gillies mitigated this by inventing the tube pedicle or “walking-stalk skin flap” technique, which involves rolling the graft to be used into a tube and “walking” it up to the target site. This technique alone likely spared thousands from infections. When the war ended, Gillies and other wartime plastic surgery pioneers were frustrated to find that their techniques and expertise were not exactly welcomed with open arms by the medical community at large. The field was not well-defined, and its practitioners had no means of sharing expertise or defining areas of specialty until the American Society of Plastic Surgeons was founded in 1931.

7 A Plastic Surgeon Helped Make Cars Safer

Debates over auto safety, which had been raging for some time prior, came to a head in 1935 with the publication of a Readers’ Digest article entitled “—And Sudden Death.” Author Joseph C. Furnas mainly took the tack of shaming careless drivers, attempting to shock them into better behavior by opining that for the reckless driver, the best hope was to be “thrown out as the doors spring open. At least you are spared the lethal array of gleaming metal knobs and edges and glass inside the car.” While it did not seem to occur to Furnas that optimizing the safety of the actual vehicle would be helpful, Detroit plastic surgeon Claire Straith arrived at this commonsense conclusion after several years of specializing in the reconstruction of faces of car accident survivors. After Straith sent a sternly worded letter to Walter P. Chrysler, five different Chrysler models were introduced in 1937 with features that were specifically designed with safety in mind, a first for any auto manufacturer. These features included rubber buttons instead of steel, rounded door handles, and recessed knobs. Although it would take a while for Straith’s other recommendations—padded dashboards and safety belts—to be implemented, it didn’t stop the good doctor from installing both in his own vehicle years before they became standard.

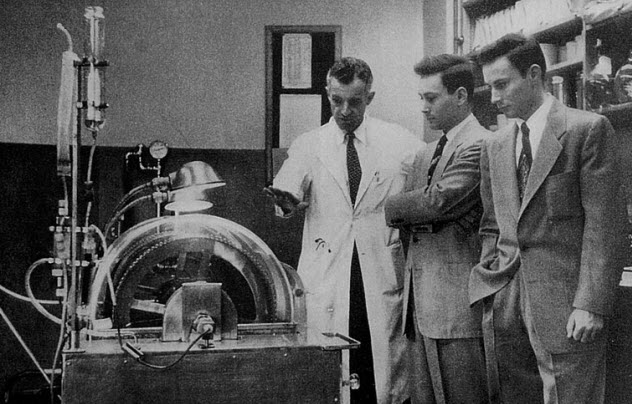

6 A Plastic Surgeon Performed The First Organ Transplant

Although most people don’t think of transplant procedures as having much to do with plastic surgery, they involve many of the same small-scale techniques, such as reconstruction and reattaching of nerves and tissue and dealing with the potential for rejection. Indeed, the first successful organ transplant of any kind—in this case, a kidney—was performed by renowned plastic surgeon Joseph E. Murray in 1954. Murray was already highly regarded for his work furthering the treatment of burn victims and those with facial disfigurements. However, this transplant procedure was incredibly groundbreaking in that, up until it was actually achieved, nobody even knew whether or not it was possible. A decade of research and experimentation on the part of Dr. Murray had failed to yield positive results. With an assist from a donor organ given by the patient’s identical twin, the successful 1954 procedure ignited the medical community with possibilities simply by establishing organ transplants as viable. Dr. Murray subsequently became an international authority on transplant and rejection biology, even helping to develop the first generation of immunosuppressants in the 1960s. In 1990, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his pioneering work. He was one of only nine surgeons, and the only plastic surgeon, to ever receive the award.

5 A Plastic Surgeon Also Performed The First Successful Hand Transplant

Dr. Warren Breidenbach, chief of the Division of Reconstructive and Plastic Surgery at the University of Arizona in mid-2016, has had a long and storied career. His current focus includes the establishment of an institute for the study of composite tissue transplantation and leading-edge work on immunosuppressants. He is considered the world’s foremost authority on hand transplants and for good reason. In 1999, he became the first surgeon to perform the procedure successfully. The recipient, Matthew Scott, had lost his hand in a fireworks accident an unbelievable 14 years prior to receiving the landmark surgery. Planning the procedure took three years. Breidenbach had to deal with the scrutiny of the entire medical community over ethics concerns as once again there were serious questions as to whether the procedure was even viable. Previous attempts—one in 1964 when immunosuppressant drugs were in their infancy and one just a year prior in 1998—had both resulted in the host’s immune system rejecting the donor hand. Since this time, over 85 recipients have received hand or arm transplants worldwide, including children, amputees, and victims of explosives. Once again, the procedure could never have come to fruition without the advances already made by plastic surgeons and it took one of the very best to do it successfully. As of 2016, Breidenbach has performed more hand transplants than any other surgeon and has trained the majority of the rest who are qualified to perform the procedure in the US.

4 ‘Medical Tourism’ For Plastic Surgery Is Exploding

As our readers in the United States know and the rest of you may have heard, the US health care system leaves a little something to be desired. Although the quality of care and technology is generally good to great, waiting times for some procedures can be excruciating, and the cost for major surgeries tends to be . . . well, an arm and a leg. As such, those in the market for expensive procedures—both cosmetic and medical—have been increasingly looking to countries where the cost of health care is more manageable. But we’re not talking about stereotypical back-alley Mexican nose jobs. Although Mexico and Brazil are still getting their share of the so-called “medical tourism” market, newer major players like Dubai and Thailand are able to offer high-tech, quality care in a price range that is actually forcing the Western medical establishment to up its game in the face of their competition. Thailand, for example, has become a world leader in medical tourism with cutting-edge equipment, internationally trained surgeons, and hospitals that look and feel more like luxury hotels than medical facilities. In 2013 alone, the country brought in a whopping $4.3 billion solely from foreigners seeking medical treatment.

3 The Newest Techniques Don’t Involve Surgery At All

Of course, for minor and less invasive procedures such as tucks and face-lifts, newer techniques are always being sought out to reduce healing time and potential scarring. New York plastic surgeon Doug Steinbrech offers a surgery-free face-lift, thanks to a special device that slowly stretches the skin over the course of three hours (under anesthesia, of course). Although stitches are required, healing is complete in five days, and the whole thing only costs $35,000, making it ideal for those who sleep on piles of money and really, really hate knives. Fellow New Yorker Dr. Doris Day—who is, of course, a local media personality with a name like that—has also demonstrated nonsurgical techniques that use ultrasound to shrink problem areas, followed by Botox and laser treatments. Ultrasound can similarly be used in place of traditional liposuction. Day calls it “the newest kid on the block for helping to resculpt and melt fat. [ . . . ] It’s like liposuction, but it’s a nonsurgical approach. [ . . . ] It uses that high-density focus ultrasound to actually heat up and melt fat.”

2 Men Are Pulling Even With Women

Most of us tend to think of surgery purely for cosmetic purposes as a largely female pursuit, and in years past, this may have been the case. But in recent times, the numbers show that a rapidly growing segment of this market—$14 billion annually as of 2014—is professional men. According to the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, between 1997 and 2014, there was a 273 percent increase in the number of men seeking cosmetic procedures, with a 43 percent increase just in the last five years of that period. A large part of the reason, says Dr. Steinbrech (him again), is that they view cosmetic surgery as a career investment. “Men are at the top of their career, and they feel young and confident,” said Steinbrech. “But they’re worried they don’t look it.” Although the huge demand for cosmetic procedures may seem absurd to some, the same techniques involved in tucks and lifts must first be mastered before going on to accomplish the near-miracles that we’ll talk about next.

1 Full Face Transplants Are Increasingly Feasible

In 2012, Baltimore plastic surgeon Eduardo Rodriguez performed the most extensive full face transplant ever done on Richard Norris, who had attempted suicide in 1997 via shotgun to the face. Needless to say, it was perhaps the most intensive and complex plastic surgery procedure ever performed up to that time. Only a few similar attempts had been made before then. The earliest—a partial face transplant—succeeded in 2006. Norris’s procedure also succeeded. Although his appearance is a bit odd and he must take drugs to keep his immune system at half-power for the rest of his life, the fact that his new face is functional given his injury is nothing short of astounding. Rodriguez has since repeated his success. In 2015, he gave a new face to firefighter Patrick Hardison, whose original visage had been completely obliterated in a fire. The results are shockingly good, with Dr. Rodriguez commenting, “Tremendous advances in medicine have occurred, tremendous advances in innovation and technology that allow us to do this procedure reliably in today’s day and age.” Although three deaths have occurred due to complications—a relatively small number given the acknowledged riskiness of the procedure—full or partial face transplants have been successfully performed on over 30 patients as of mid-2016.