This list is partially, but not exclusively, in chronological order, because many of the most important changes in the vice-presidential office have occurred more recently. It also shows the progression of the vice-presidency from a mostly powerless, ceremonial office to its current form today.

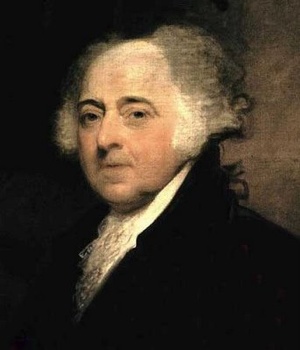

In 1789, the electoral college met for the first time ever to choose a President of the United States. One of the presidential hopefuls that year was John Adams, the ambitious lawyer and diplomat from Massachusetts. Unfortunately for Mr. Adams, all 69 members of the electoral college voted for George Washington as the first president. But in these days, there was a catch – – the electoral college had to cast a second ballot for a different individual from a different state… so despite Washington’s 69/69 blowout, the electors had an additional 69 votes to cast. 34 of these votes went to Mr. Adams. As the runner-up to Washington, he became the first Vice President (as the Constitution mandated prior to the 12th Amendment in 1804). Adams’ tenure as Vice President was relatively unremarkable. Washington kept him out of his cabinet meetings and rarely consulted him as an advisor. Instead, he was stuck presiding over the senate, with no voice or vote except in the rare case of a tie. He absolutely hated the job. But despite his uneventful tenure, Adams is important simply because he was the first guy to hold the office. He set a precedent that, to some extent, all subsequent holders of the office have followed. Adams was also the first Vice President to be elected President later, a tradition that many others have followed (or at least attempted). Just think though – – if the runner-up to Washington had been John Jay or Robert Harrison instead of Adams, the vice-presidency might have evolved into something completely different today… so it’s important to recognize its roots with Mr. Adams over two centuries ago.

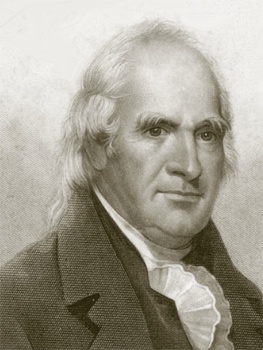

In 1804, then-president Thomas Jefferson breathed a sigh of relief as the 12th Amendment to the US Constitution was ratified. The amendment stated that the Vice President would be chosen on the same ballot as the president, replacing the old system of having the runner-up take the office. Jefferson was stuck with a loose-cannon Vice President that he didn’t choose – – Aaron Burr. Matters only got worse when Burr shot and killed Alexander Hamilton. But with the 12th Amendment, Jefferson was given the ability to choose his vice-presidential candidate in his upcoming re-election campaign, and that man was George Clinton, the Governor of New York – – who became the first Vice President elected as a member of a presidential ticket. Like John Adams, Clinton was largely ignored by the president and his advice was rarely sought. His only consistent duties were as the presiding officer of the Senate, which were largely uneventful. But for Jefferson, this wasn’t a problem. In Clinton, he had exactly what he wanted – – a Vice President who didn’t cause problems for the president. This has become a major concern of presidential hopefuls in picking a running mate to this day. Clinton did such a swell job as Jefferson’s do-nothing Vice President, that James Madison decided to choose him as his own running-mate in 1808. This made George Clinton the first Vice President to serve under two presidents (the other was John C. Calhoun). In 1812, Clinton also became the first Vice President to die in office. Since Madison was running for re-election that year, he chose Elbridge Gerry as his new running mate, who in 1814 became the second Vice President to die in office.

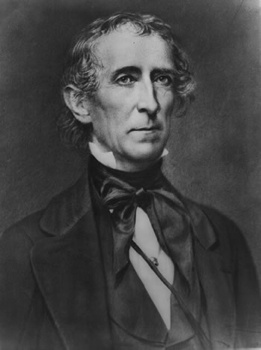

John Tyler became Vice President on March 4, 1841. He held this office for a whopping thirty-two days. Nevertheless, Tyler’s vice-presidency created one of the most important precedents of the office. On April 4, President William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia after a largely uneventful month-long tenure as Commander-in-Chief. This caused a bit of a succession crisis. Article II, Section I of the US Constitution states that in the case of the president’s death or removal from office, that his duties will be “devolved” onto the Vice President. The vagueness of the clause left was much disagreement as to what degree Tyler was actually president. Some considered him to be simply “Acting President” and could only hold the office as a caretaker until Congress called for a special election, or appointed a different individual to be president. Others considered him to be the legitimate president, and would serve the remainder of Harrison’s term. This was exactly the position that Tyler held, and said that he was the 10th president of the United States and nothing less. He served as president until 1845, setting a precedent that in the case of a president’s death or removal, that his Vice President would take the office and serve the remainder of the term. Since then, there have been eight other Vice Presidents to become president under similar circumstances.

For most of the 19th Century, the vice-presidency was largely powerless and ceremonial. A big exception to this was William McKinley’s Vice President, Garret Hobart. Even though he still regularly carried out the main task of presiding over the Senate, Hobart was regularly consulted by McKinley for assistance and advice. In 1898, it was Hobart who ultimately convinced McKinley to urge Congress to declare war on Spain. He also cast the tie-breaking vote in the Senate which decided to take the Philippines as an American territory once the war ended. As Vice President, Hobart’s active role proved to be popular with fellow politicians. However, he died unexpectedly in 1899 and left the seat vacant until McKinley’s re-election a year later, when Teddy Roosevelt took the office.

As the 20th century progressed, the vice-presidency was still a largely unimportant component to the executive branch. In 1940, Franklin Roosevelt ran for a third term as president, and dropped his Vice President, John Nance Garner, from the presidential ticket that year and replaced him Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace. After winning the election that year, Roosevelt opted to give Wallace a more active role in his administration by naming him to various other posts such as the Board of Economic Welfare. Wallace quickly became an important figure as the United States entered World War II, as he strongly supported the war effort and sought to defeat the Nazis. He also was an outspoken and vocal supporter of Civil Rights at this time. Of course, since Roosevelt’s coalition depended heavily on Southern Democrats who favored segregation, Wallace’s open opposition to it became problematic. Additionally, Wallace became increasingly friendly with the Soviet Union and advocated a stronger alliance with Stalin. This was the last straw for Roosevelt, and he dropped Wallace from the presidential ticket in the 1944 election.

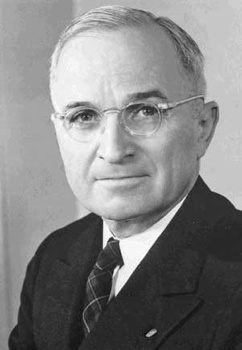

Since Franklin Roosevelt viewed his experiment with Henry Wallace as a more active Vice President as a failure, when he was re-elected to a fourth term in 1944, he decided to give his new Vice President, Harry Truman of Missouri, a more traditional “do-nothing” role as presiding officer of the Senate. Truman, a former senator, found himself in a position that he didn’t like, and complained that the job of the Vice President was to “go to weddings and funerals.” Of course, after only three months in office, Roosevelt died and Truman became president. Upon taking office, Truman was informed of the development of the Atomic Bomb, something that Roosevelt’s administration never bothered to tell him about. This realization made Harry Truman re-think the importance of the vice-presidential office… which in the post-war world could no longer be dismissed as insignificant and ceremonial. In 1947, Truman created the National Security Council, in which the most important matters of national security would be discussed. After he was elected to a second term in 1948, which filled the vice-presidential vacancy left by Truman, he made sure that new Vice President Alben Barkley was included as a member of the National Security Council and had him attend cabinet meetings as well. Even though Truman’s vice-presidency was short and uneventful, Roosevelt’s sudden death allowed him to realize of how essential it was to keep the Vice President informed of the nation’s most important issues. For this reason, Truman must be included one of the most important Vice Presidents of all-time.

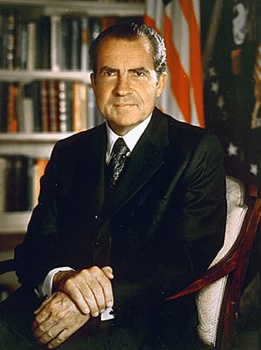

The 25th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified in 1967, which gives the president the power to nominate a new Vice President if the office has become vacant, if it is approved by Congress. In October of 1973, President Richard Nixon’s Vice President, Sprio Agnew, abruptly resigned after allegations of bribery and tax evasion. This gave Nixon the first-ever opportunity to exercise the powers of the 25th amendment, which he subsequently did by nominating Representative Gerald Ford of Michigan. Ford was a moderate Republican whose nomination was met with little opposition in Congress, which quickly approved of Nixon’s choice, allowing him to be sworn-in on December 6, 1973. As the following year progressed, revelations in the growing Watergate scandal made it seem increasingly likely that Ford might end up as president in the case of Nixon being impeached or resigning. As a result, Ford was given a very keen sense of presidential duties in preparation for such an event, and is perhaps the only Vice President to be given advanced warning of a coming presidential vacancy. Nixon finally did resign on August 9, 1974, and Ford succeeded him as the only individual to hold the office without being elected president or Vice President.

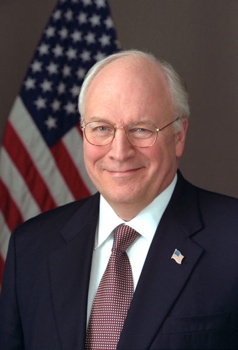

An extremely controversial figure, Dick Cheney served for eight years as George W. Bush’s Vice President. During the 2000 election, it was sometimes joked that Bush was in fact Cheney’s running-mate, and this continued with allegations that Cheney was the real “power behind the throne” (which are a bit farfetched, as Cheney often voiced impatience and frustration with many of Bush’s decisions, especially Bush’s refusal to grant Cheney’s friend Scooter Libby a presidential pardon). Even still, Cheney was an especially powerful vice-president, who as a former Secretary of Defense, advised Bush on defense and national security issues, and is heavily credited as one of the main architects of the Iraq War. He was also known for having been especially shrewd as a politician. He was quick to make pointed attacks on his opponents, and in 2005 several members of his staff (in particular, Scooter Libby) were investigated for leaking the identity of a CIA agent that had angered Cheney (see the Plame Affair for more on this). At the end of his term, Dick Cheney was widely recognized as one of the most unpopular Vice Presidents in American history among Republicans and Democrats alike. Despite this, it is without a doubt that he was one of the most powerful individuals to hold the office, and it remains to be seen how his tenure will influence the office in the years to come.

Following Harry Truman’s post-war reinvention of the vice-presidency, President Dwight Eisenhower decided to take things to an even higher level for his Vice President, Richard Nixon. Even before Eisenhower was elected, Nixon was a visible campaigner and in response to a small scandal regarding political gifts, became the first vice-presidential candidate to release his tax returns to the public. As Vice President, Nixon was given the task of actually running cabinet meetings in the absence of Eisenhower, and Nixon acted on his behalf during two occasions when Eisenhower suffered a heart attack, and then a stroke. This was a full decade prior to the ratification of the 25th amendment, which covers times of presidential disability or incapacity – – but Eisenhower firmly outlined directions in which Nixon would assume temporary presidential powers during such events. Even though Nixon was given new powers and responsibilities, like many of his predecessors, he was still largely confined to the business of presiding over the Senate. But his vice-presidency was certainly an important step forward in the development of what the office is today.

Right now, it seems that Walter Mondale might be destined to be one of those in the long line of forgotten Vice Presidents. A one-term Vice President and the badly-defeated 1984 Democratic candidate for the presidency, he just doesn’t have the same interesting narrative of Harry Truman, Richard Nixon, or Al Gore. But what is often overlooked is that Walter Mondale was, without a doubt, the first truly modern Vice President of the United States. As a Senator from Minnesota, he was chosen by Jimmy Carter to be his running-mate in 1976. After winning that election, Carter gave Mondale a very different role in his administration. Vice President Mondale was not expected to preside over the Senate (except in rare cases such as counting electoral college ballots, or breaking tie votes). He was the first Vice President with an office in the West Wing of the White House, where he was commonly consulted by the President on all issues, whether it was domestic, foreign or defense. Carter encouraged Mondale to voice his own opinions and disagreements in meetings, as to offer a different point of view. Also, with the national security concerns of the Cold War, as Vice President he received intelligence briefings on a daily basis – – a tradition that carries on to this day. Jimmy Carter was badly defeated by Ronald Reagan in 1980, but the Mondale legacy survived. Reagan kept Carter’s reforms of the Vice Presidential office, and so have the subsequent presidents since then. The final result is that after Walter Mondale, the Vice President was no longer a ceremonial sidekick, but the actual partner, confidant and teammate of the President.