One strange animal is even reminiscent (to paleontologists, at least) of a character played by actress Natalie Portman. Others are just as odd and intriguing, and several of these ten incredible ancient animals have overturned scientific beliefs while expanding the knowledge of life as it existed millions of years ago.

10 Predatory Whales

New evidence provided by 3-D scans of digital simulations of fossilized baleen whale teeth suggests that in the past, these whales weren’t the gentle giants we know today. The mouths of modern baleen whales contain “bristle-like structures” to strain plankton and small fish from seawater. Their ancient forebears, however, were equipped with sharp teeth with cutting edges. According to Erich Fitzgerald, the senior curator of vertebrate paleontology at Museums Victoria, “These results are the first to show that ancient baleen whales had extremely sharp teeth with one function—cutting the flesh of their prey.”[1] It had been theorized that these ancient toothy whales closed their jaws and used their teeth to strain prey from the ocean, leading to the evolution of the more familiar form of filter feeding. This is no longer believed to be the case.

9 Pectinatella Magnifica

Pectinatella magnifica, also called the magnificient bryozoan, is a brownish-gray, slime-filled hermaphrodite with a pineapple-like texture and an odd, brain-like shape. The species was recently found in Canada’s Lost Lagoon in Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia. Stanley Park Ecology Society’s Celina Starnes waded into the lagoon, where she plucked one of the animals from its hiding place. Starnes said the creature felt gelatinous, like Jell-O. Besides its strange appearance, the bryozoan has several other bizarre characteristics. Each one of the seemingly single organisms is actually a colony comprised of of hundreds of creatures, a single one of which, called a zooid, is less than a millimeter in size. P. magnifica is hermaphroditic and can also reproduce asexually, if a cluster of its cells, called a statoblast, breaks off. Before this find, P. magnifica was thought to only exist east of the Mississippi River. No one knows whether the bryozoans have always lived in the Vancouver region, going undocumented until recently, or whether they found their way into Canada when climate change led to warmer temperatures, allowing the creatures to spread north. Bryozoans have been around for at least 470 million years and feed on algae, which they filter from the water. They can be hazardous to the environment, upsetting the freshwater ecosystem’s balance, and they tend to clog pipes. They’re also known to leave a thick film of mucus behind after they’re handled.[2]

8 Eusaurosphargis Dalsassoi

An artist’s conception of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi, based on a complete fossil of the ancient creature, shows a reptile with a rounded body, a flaring tail, and rows of spikes along its back. In appearance, it resembles today’s girdled lizards. It’s likely the armored animal didn’t swim well, if at all. Probably, it was a landlubber, making its home ashore rather than in the water. The fossil was found in the Swiss Alps, which further negates the earlier view of the creature’s aquatic nature. The 20-centimeter-long (8 in) fossil, perhaps that of a young animal, suggests that the lizard crawled on “spadelike claws” propelled by stiff-jointed legs. The animal’s mode of locomotion and its coloration also indicate a terrestrial, rather than an aquatic, habitat.[3]

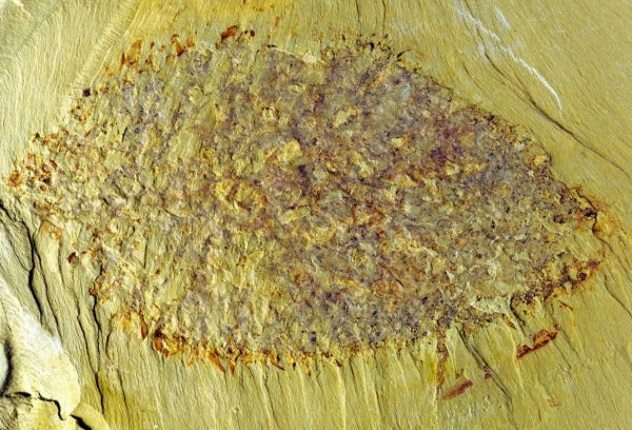

7 Nidelric Pugio

A strange balloon-shaped animal defended by an “outer skeleton” armed with spines, this fossilized chancelloriid was unearthed in China. The 520-million-year-old fossil in the shape of a “squashed bird’s nest” promises to increase scientists’ knowledge of ancient sea life. A bit over 9 centimeters (3.5 in) in length, this example of Nidelric pugio flattened into its present “squashed” form during its fossilization. The species was named in honor of the late Professor Richard Aldridge, a paleontologist and ornithologist formerly of the University of Leicester’s Department of Geology. Nidus is Latin for “bird’s nest,” and “adelric” is derived from the Old English name “Aedelic” (a source for the name “Aldridge”), with “adel” meaning “noble”) and “ric” meaning “a ruler.” Dr. Tom Harvey of the University of Leicester said that the rare fossil is valuable because it demonstrates “how strange and varied the shapes of early animals could be.”[4]

6 Mysterious Lizards

Two ancient lizards encased in amber represent mysteries for opposite reasons. The place of origin of one is known, but its identity is not; the other’s identity is known, but not its place of origin. The former’s fossil is a mere outline: Its skin is intact, but its internal organs are “lost to time.” It was found in the fossil-rich Hukawng Valley of Myanmar, the location of 99-million-year-old Burmese amber where previously, an ancient baby bird, a dinosaur tail with feathers, and a bizarre insect were documented. Because of the lizard’s missing entrails, scientists have no clear idea as to whether it’s “a skink, gecko, or something else,” said Kelsey Jenkins, a graduate student at Sam Houston, admitting that the fossil is “a puzzle.” The other fossil, which sat in a Canadian museum for years with no documentation, is that of a gecko, its skin, skeleton, and characteristic toes and claws clearly establishing its identity. Where it made its home is what’s not certain. Researchers hope a chemical analysis of the amber associated with the specimen and of the spider trapped inside with the fossil may provide clues to its place of origin. The amber’s composition suggests a tropical environment.[5]

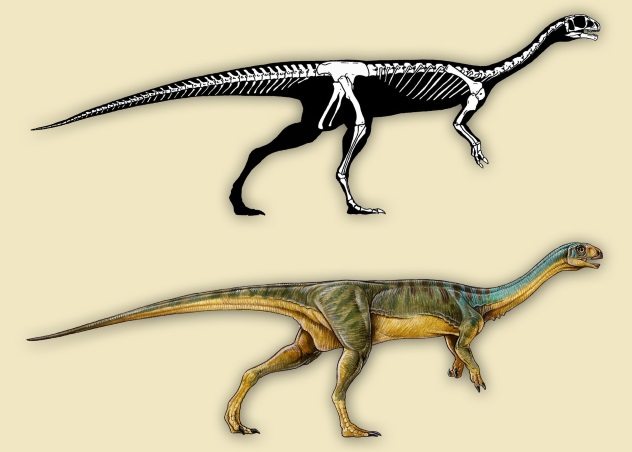

5 Chilesaurus Diegosuarezi

It’s difficult to imagine a “vegetarian” T-rex, but one of the monstrous dinosaurs’ relatives, Chilesaurus diegosuarezi, consumed only plants. It had other bizarre attributes as well. For one thing, it has features characteristic of a number other prehistoric creatures. The size of a horse, C. diegosuarezi was more plentiful than any other animal alive 145 million years ago in what’s now Chile’s Aysen Region. Fernando Novas of the Bernardino Rivadavia Natural Sciences Museum in Buenos Aires finds the animal mystifying. “I don’t know how the evolution of dinosaurs produced this kind of animal, what kind of ecological pressures must have been at work,” he admits. The bones of a dozen of the animals were found near General Carrera Lake in Southern Chile. Four of the specimens were almost fully preserved. Once a carnivore like Tyrannosaurus rex, velociraptors, and other theropods, C. diegosuarezi altered its diet, becoming a herbivore, as evidenced by its horny beak, flat teeth, small head, and slender neck, quite unlike the heads and necks of typical of meat-eaters. Chilesaurus diegosuarezi also had forelimbs more like an allosuarus, albeit with “two stumpy fingers” in lieu of sharp claws. Its bizarre mixture of features indicates it to be “an extreme example of mosaic convergent evolution, where different parts of an animal adapt to the environment along the same path taken by other creatures.”[6]

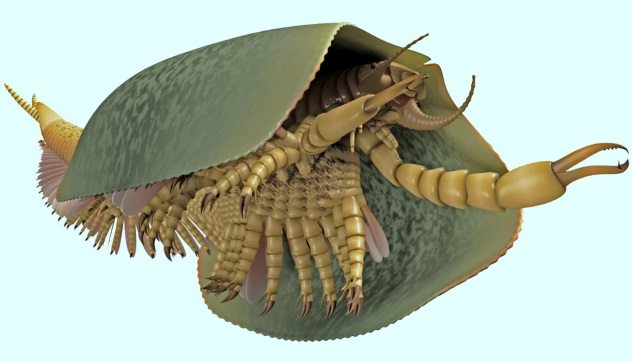

4 Tokummia Katalepsis

A rolled, semicircular shell on the back of a strange, segmented, slug-like body with antennae and rippling, rib-like tissues on its underbelly; a bevy of segmented legs enabling it to walk on the ocean’s floor; and claw-like appendages at its rear make Tokummia katalepsis a bizarre-looking sea creature. Found in 2017 by a team of paleontologists from the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum, the fossil of this ancient creature helps better to explain mandibulates, animals equipped with mandibles, which include flies, ants, crayfish, and centipedes. The newly uncovered fossil was named for Tokumm Creek in Marble Canyon in Kootenay National Park, British Columbia, and the Greek word for “seizing.” The strange sea creature, which measures over 10 centimeters (4 in), lived half a billion years ago. Although it was able to swim, scientists believe it preferred to live on the bottom of the sea. Cedric Aria, the lead author of the study and a recent PhD graduate of the Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology program at the University of Toronto, said the creature’s “large, yet delicate and complex” pincers are reminiscent of “can openers” and were “adapted to the capture of sizable soft prey items, perhaps hiding away in mud.” Its segmented limbs ended with tiny projections called endites and were evolutionary precursors to the legs of mandibulates.[7]

3 Tamisiocaris Borealis

Tamisiocaris borealis, a 0.6-meter (2 ft), 520-million-year-old prehistoric shrimp, had “bizarre feeding filters built into its face.” The Cambrian creature inhabited the waters off modern-day Greenland and ate in the manner of the modern blue whale. Its means of feeding itself was unique among similar species of the Cambrian period. The marine animal swept seawater with its pair of facial appendages to filter and trap plankton, analogous to how blue whales use their baleen to strain particles of food from seawater. A “gentle” predator, the shrimp’s sweeping the water for food caused it to expend a lot of energy, so it had to eat a large quantity of plankton. The documentation of Tamisiocaris borealis puts to rest paleontologists’ former belief that anomalocarids represented an “evolutionary failure.” Now, these scientists believe that instead, they underwent an explosive evolutionary development, permitting them to become top predators.[8]

2 Xenokeryx Amidalae

Scientists have named an bizarre male animal equipped with three horns atop its head after Star Wars character Queen Amidala, portrayed by Natalie Portman. Xenokeryx amidalae lived 15 million years ago in Europe. The largest horn of the well-preserved fossil of Amidala’s namesake resembles a hairdo worn by the character in the first episode of the science fiction series. The females of the species lacked horns and fangs, but the males had small horns above either eye, a larger, T-shaped bone on the back of their heads, and enlarged canines, which were probably used for display purposes. The size of deer, X. amidalae was a herbivore living in grasslands along rivers, subsisting on a diet of leaves, fruits, and roots. Its closest relatives today are the giraffe and okapi, but Xenokeryx amidalae lacked its descendants’ long necks. Like cattle, sheep, goats, deer, giraffes, and okapi, the ancient animal was a ruminant: It had a stomach of four compartments and chewed cud.[9]

1 Puentemys Mushaisaensis

Curiously, a huge 60-million-year old South American turtle called Puentemys mushaisaensis had an almost perfectly round shell, which would have made it “more than a mouthful” for Titanoboa cerrejonensis, a snake that could reach 14 meters (45 ft) in length. Found in Colombia’s La Puente pit in the Cerrejon Coal Mine, where other notable fossils have been unearthed, the giant fossilized turtle, named for the pit, had a shell measuring 1.5 meters (5 ft) across, suggesting that turtles achieved great size once dinosaurs became extinct. They grew to huge dimensions in the absence of predators and in the presence of abundant food, a large habitat, and other factors. The turtle’s shell protected it both from Titanoboa and other predators as well as from cold temperatures. The shell’s low dome allowed it to catch more sunlight, helping the cold-blooded turtle to stay warm. “The shell was far more rounded than a typical turtle,” said researcher Carlos Jaramillo of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama.[10]